From Partition to Protest: The Revolutionary Journey of Khawaja Ijazullah

A Personal Tribute by Mukhtar Dar

Writing a tribute to Aijaz Kaleem humbles me deeply. How does one capture the essence of a man whose life and work profoundly shaped my political consciousness and redefined my understanding of the world? Aijaz would have resisted such a spotlight, especially considering his firm opposition to the cult of personality and what he referred to as "petty bourgeois individualism." To honour him in a manner befitting the values he held so dear, I must carefully balance my admiration with respect for the collective struggle to which he devoted his life.

Aijaz never sought recognition; he was steadfastly opposed to opportunism and those who compromised their principles for the sake of accolades within the British Empire’s honorary system. He was an anti-imperialist and revolutionary in the truest sense—selfless, dedicated, and unwavering in his focus on the greater cause. Every ounce of his energy and every moment of his life was devoted to the pursuit of a better world. His life stood as a testament to the power of conviction grounded in social justice and equality, and it was this unwavering commitment that first drew me to him. His influence has guided me ever since.

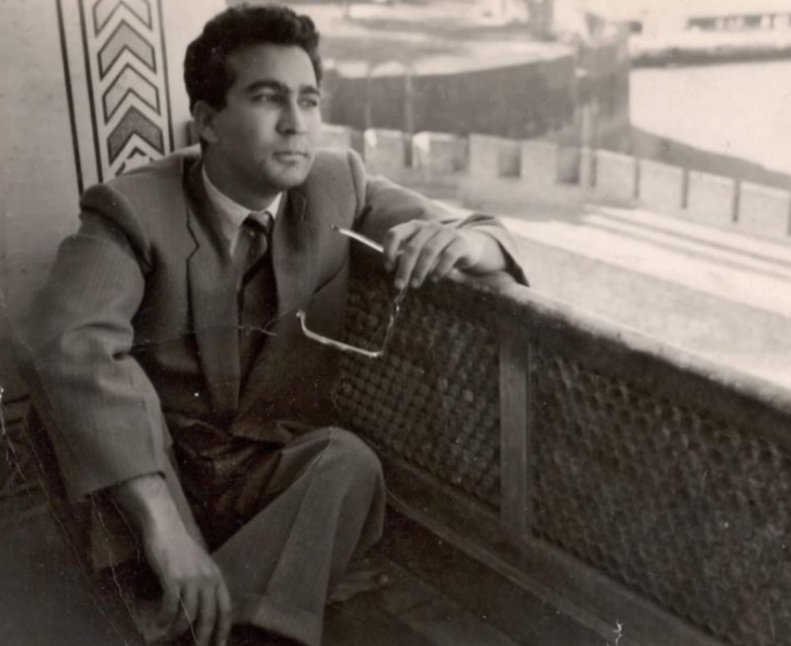

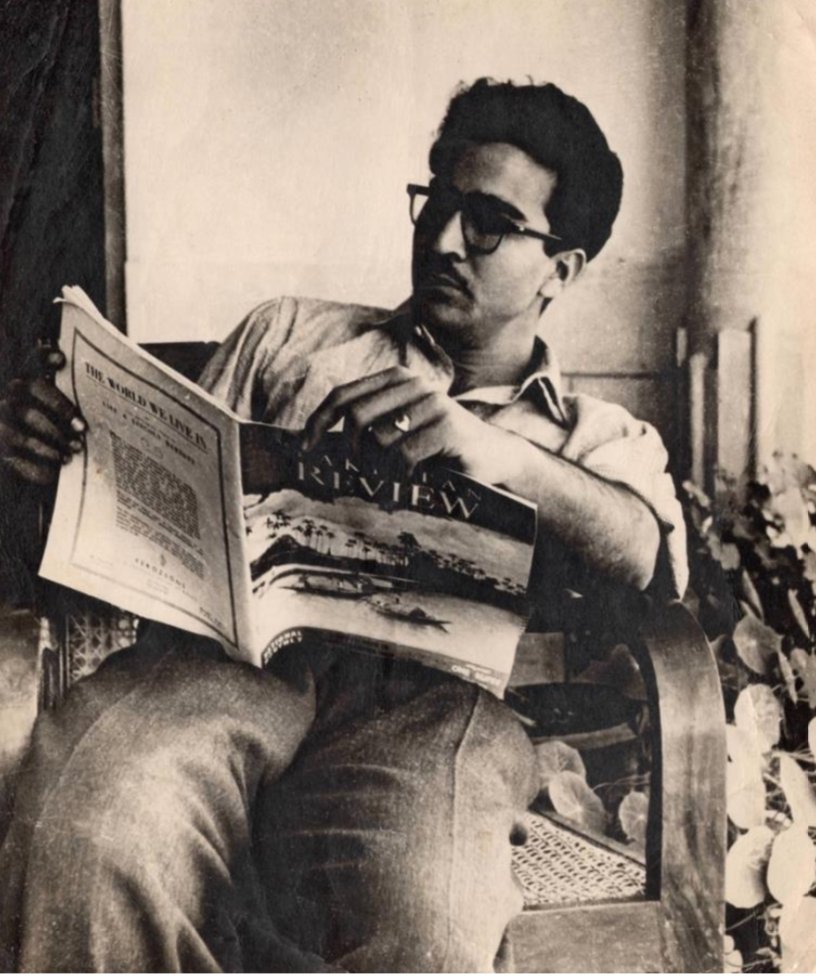

Aijaz was born on February 14, 1937, in Banga, Jullunder District, in what is now East Punjab, India. His life was deeply marked by experiences that would shape his worldview. Raised modestly by his father, an art teacher, Aijaz’s childhood was irrevocably altered by the Partition of India in 1947, which forced his family to migrate to the newly formed state of Pakistan. At the age of nine, he witnessed the horrific communal violence of Partition, where the butchered bodies of his Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh school friends, as well as the blood-soaked trains carrying corpses on both sides, became haunting memories. These traumatic events cast a long shadow over his life, leaving him with a silence he seldom chose to break.

Despite these early hardships, Aijaz displayed remarkable resilience. He attended school in Wazirabad and later pursued college in Lahore, but financial constraints forced him to abandon a Master’s degree in English Literature. In 1963, he migrated to the UK, where he worked a series of temporary jobs in London before joining the Post Office as a parcel sorter. The bustling streets of London during the 'Swinging Sixties' were a world away from the quiet alleys of Wazirabad, and it was here that Aijaz’s worldview began to expand in unexpected ways. The shared house he lived in with other migrants from the Caribbean, Africa, and the subcontinent was more than just a roof over his head—it was a microcosm of global struggles, a place where stories of resistance, colonial histories, and dreams of liberation were exchanged in the dim light of late-night conversations.

In the company of these fellow workers, Aijaz found kindred spirits. Over shared meals and stolen moments of rest, they spoke of lands left behind and futures imagined. The civil rights movement in the United States, the relentless protests against the Vietnam War, and the rising tide of anti-colonial struggles across Africa and Asia—these were not distant events, but the very pulse of their daily lives. London, with its swinging nightlife and counterculture, was a city in flux, much like Aijaz himself. The experiences of the ‘Swinging Sixties’ became a crucible in which his ideological beliefs were forged, deepening his commitment to global Black and Third World movements.

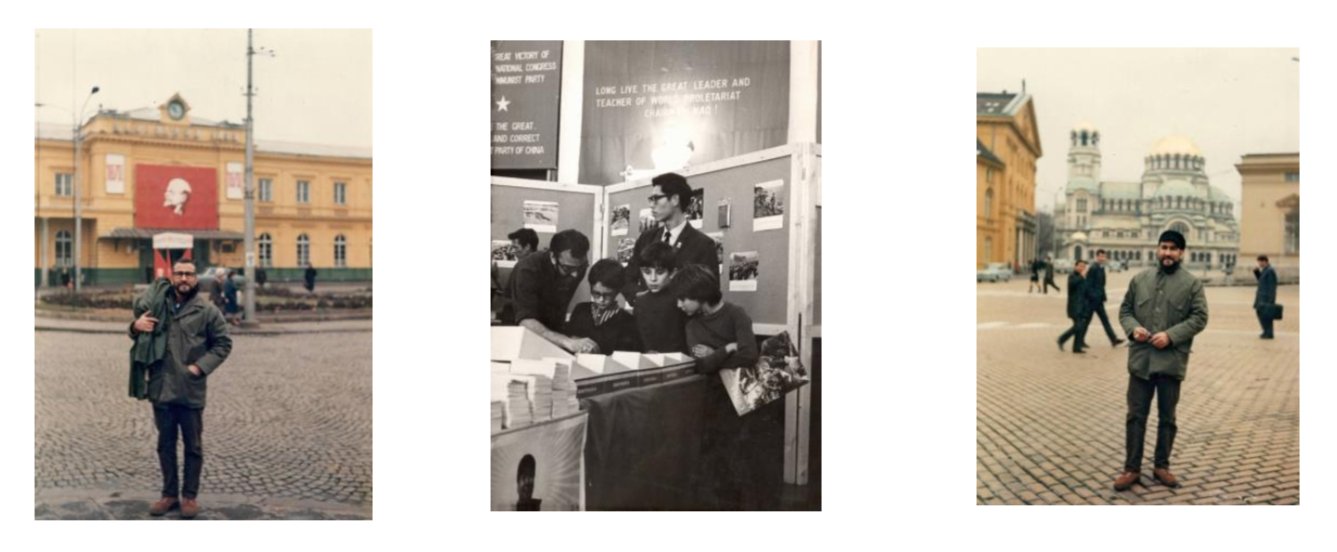

Vietnam, with its jungles and defiant peasants, became more than just a name in the news; it symbolised resistance against imperial power. One of the earliest protests Aijaz participated in occurred on March 17, 1968, when he joined 25,000 others in an anti-Vietnam War demonstration outside the US Embassy in Grosvenor Square. The protest culminated in running battles between police and demonstrators. In the aftermath of these events, Marxism-Leninism, once an abstract ideology, gained vivid urgency, offering Aijaz and his comrades a lens through which to understand their own struggles. The Chinese Cultural Revolution, with its emphasis on rural peasants as the driving force for societal change, resonated deeply with Aijaz’s growing belief in the need for radical transformation.

A chance meeting with a friend from India who ran a left-wing bookshop in London led Aijaz to volunteer there, where he met the late great Jagmohan Joshi, then General Secretary of the Indian Workers Association. Joshi also ran a bookshop, ‘Progressive Books and Asian Arts,’ in Birmingham, and in 1972, Aijaz moved to Birmingham to assist him. He became part of an extended Birmingham-based Revolutionary Communist League, a diverse group of revolutionaries, many of whom became his lifelong friends and comrades. At the same time, he enrolled as a mature student to study sociology at the City of Birmingham Polytechnic, where he met his life partner, Phyllis Brazier.

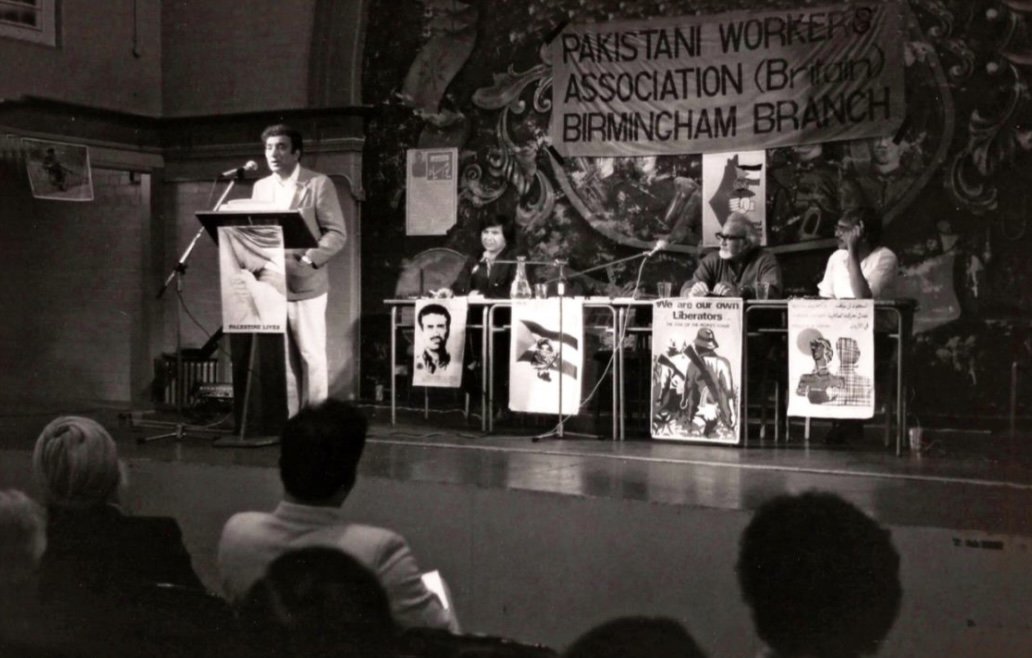

In 1979, while working as an advice worker at the Asian Resource Centre in Handsworth, Aijaz used his language skills to support local communities by translating leaflets, inspiring campaigns, and forging broad alliances among community groups and political organisations. By the 1980s, he had become a founding member of the Pakistani Workers Association (PWA) and the editor of its monthly journal, Paikaar. The PWA was an independent political organisation that emerged from the anti-racist struggles in the UK and identified itself as a Black political organisation. The PWA’s stance against state funding attracted many former members of the Asian Youth Movements. At the forefront of numerous anti-racist campaigns, the PWA forged a formal alliance with the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, initiated by Kwame Ture (formerly known as Stokely Carmichael), then the honorary Prime Minister of the Black Panther Party in America.

Under Aijaz’s editorial leadership, *Paikaar* was published in both English and Urdu, with Aijaz painstakingly translating and handwriting articles in Urdu. The journal featured articles and analysis aligned with the three pillars of the PWA: the struggle of the Pakistani diaspora as an integral part of Black people's fight against racism in the UK, support for the progressive struggles of national and religious minorities in Pakistan, and solidarity with worldwide movements of oppressed peoples and nations against colonialism and imperialism. *Paikaar* was printed in an industrial unit in Hockley, Birmingham, on a specially reconditioned printing press named "Skylark," after the anthology of poems by Irish revolutionary hunger striker Bobby Sands. Aijaz’s love of literature and poetry was evident in the pages of *Paikaar,* with the centre spread often dedicated to revolutionary poetry from around the world. I had the privilege, under the pen name Mazour Dar, of illustrating the poetry and designing the journal's overall graphics, including the front cover while Phyll, under the pen name Frida Banu, used her writing and editing skills to proofread, edit, and compile many of the articles.

One of my most enduring memories of Aijaz is seeing him on Watford Road, tirelessly engaging with members of the Pakistani community about our antiracist struggle for survival with dignity while challenging the military dictatorships in Pakistan. Whether in rain, snow, or sunshine, Aijaz was always out there, alongside other branch members, selling *Paikaar* and fostering an understanding of our communities across the different branches. Aijaz was a fearless anti-racist fighter, and together with Phyll, he was deeply involved in many local and national anti-deportation campaigns, as well as efforts against racist attacks, murders, and the criminalisation of our people when they defended themselves against racist violence. Their work included campaigns like the case of Satpal Ram, who defended himself against a racist attack and was convicted of killing Clarke Pearce in a restaurant in Lozells, Birmingham, in 1986, and the case of Ashiq Hussain, a 21-year-old Birmingham taxi driver who was stabbed to death in 1992 after coming to the aid of another driver being racially abused. They also supported the family of Tasleem Akhtar, an 11-year-old brutally murdered near her home in Sparkbrook by a 16-year-old who had previously attacked many other Asian children. In addition to these campaigns, Aijaz and Phyll worked closely with Shirley Joshi, the wife of Jagmohan Joshi, to build an anti-racist united front through the Birmingham Campaign Against Racism and Fascism.

In addition to their anti-racist work, both Aijaz and Phyll were deeply involved in international solidarity efforts, supporting national liberation struggles in Ireland, Palestine, and Kashmir, as well as anti-war campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan. Through these efforts, they won the respect and developed enduring friendships with families who had lost loved ones or been displaced by the imperialist wars that had been unleashed in the Global South. I first crossed paths with Aijaz in 1985, at the age of 24. As a young and eager member of the Sheffield Asian Youth Movement, I had spoken on behalf of the Newham 7 Campaign at a meeting in the New Inn Pub in Handsworth, Birmingham. That night remains etched in my memory, not just because it marked the beginning of my relationship with Aijaz, but because it introduced me to a world I had never imagined possible.

The New Inn Pub was a place unlike any I had ever seen—a vibrant, revolutionary space where cultures, ideas, and movements collided in a cacophony of resistance. In the courtyard, Jamaican Rastafarians chanted down Babylon on a sound system, their voices echoing with the power of four centuries of struggle against the Babylonian system. In another room, Indian factory workers, members of the Indian Workers Association, recited revolutionary Naxalbari Punjabi poetry, their words flowing with the strength of their convictions. They drank Bacardi, JD whiskey, and coke brought through a shared kitty, their camaraderie as intoxicating as the spirits on the table. Meanwhile, white men and women sang Irish republican songs and English ballads of working-class struggles, their voices weaving together the diverse threads of resistance into a tapestry of solidarity.

Coming from a close-knit Pakistani community in Sheffield, where I had to avoid being spotted by taxi drivers who might report my pub visits to my father, stepping into the vibrant world of Handsworth was nothing short of a revelation. Here, the pubs were not only filled with Asians but were owned by them, brimming with a revolutionary fervour that shattered the boundaries that had once confined me. In this electrifying atmosphere, I was free to immerse myself in the struggle for justice alongside comrades from every walk of life. This experience inspired me to make Birmingham, and specifically Handsworth, my home—a place where community centre walls proudly displayed posters of revolutionary freedom fighters like Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Angela Davis, Jayaben Desai, James Connolly, and Bobby Sands. It was a place where I visited mosques, mandirs, gurdwaras, and churches not to pray, but to talk about the inner-city uprisings and our struggle for justice—a place where I could live the revolution I had only dreamed of. And it was Aijaz who became my guide on this transformative path.

Upon moving to Birmingham, full of youthful energy and revolutionary zeal, I joined the Birmingham Asian Youth Movement. It was a time of heightened class struggle and resistance, and I found myself renting a small upstairs flat on Hamstead Road, just off Lozells Road, in the heart of the notorious frontline of Handsworth and Lozells. This was a community in struggle, a place where the pulse of resistance beat strongest. It was here, in 1985, that the second Handsworth inner-city rebellion erupted, sparked by the arrest of a Caribbean man near the Acapulco Café and a brutal police raid on the Villa Cross Pub across the street. The streets where I lived were not just a battleground—they were a crucible, forging bonds of solidarity and shaping the consciousness of a new generation of activists.

In this environment of struggle and solidarity, the Asian Youth Movement (AYM) became my true home. We held our weekly meetings at the Asian Resource Centre on Lozells Road, just a stone's throw from the Acapulco Café. Our evenings often found us in the same pubs as comrades from Birmingham Black Sisters, the Indian Workers Association, the African Caribbean Self Help Organisation, and other local collectives and self-help organisations, including creative visionaries, dub poets, writers, and griot storytellers who wove the history of our people. These were not merely social gatherings; they were extensions of our activism—spaces where the lines between personal and political blurred, where strategies were discussed, alliances forged, and dreams of a just world nurtured over pints and poetry.

One night after closing hours at the lock-in at the Village Maid Pub off Villa Road, Billu Bassi and I—both committed members of the AYM—had been deep in conversation, inspired by the possibilities of our shared struggle, Aijaz and Phyll invited us to continue the discussion back at their home in Edgbaston. I had met Aijaz and Phyll on several occasions before, but it was that night when our relationship truly deepened. Billu stayed at Aijaz’s house for a couple of days, but I, intending only to stay for the evening, ended up remaining for a couple of years. That night marked the beginning of a long and enduring friendship, and the start of Aijaz and Phyll becoming not just my comrades, but my extended family and my mentors.

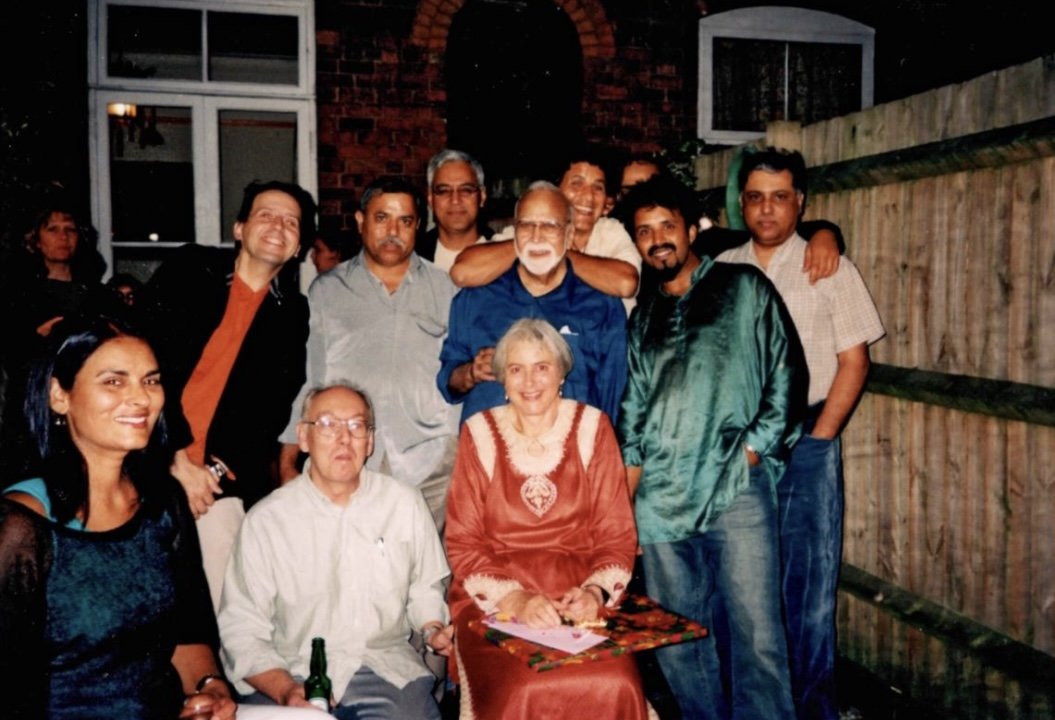

Aijaz’s home, shared with his life partner Phyll, was far more than just a residence; it was a sanctuary of revolutionary thought and action, a vibrant hub where the personal and political intertwined seamlessly. Revolution wasn’t merely a topic of discussion here—it was lived. The walls, lined with bookshelves overflowing with texts on Marxist theory, history, literature, and poetry, and adorned with posters of revolutionary leaders and movements, served as constant reminders of the struggles that defined their lives. Nestled in the heart of Edgbaston, this house became my true home, not just physically but ideologically and emotionally. It was a space where countless discussions, debates, and dreams aimed at changing the world unfolded, with Aijaz always at the centre, guiding all who entered with his boundless energy and sharp intellect.

In Aijaz, I found a father figure, friend, comrade, and mentor—someone whose influence extended far beyond the transfer of knowledge. He was a teacher who built consciousness and critical thinking, embodying his convictions with passion that was both inspiring and humbling. In this space, I learned the true meaning of solidarity, not as a theoretical concept, but as a way of life. Aijaz and Phyll’s home was open to all who were committed to the cause. It was a refuge for those fleeing deportation, a place where strategy meetings extended late into the night, punctuated by obligatory poetry readings and shared meals. Revolution, I realised, was not just about fighting oppression, but about creating new forms of human relations, where care, compassion, and camaraderie were at the heart of everything we did.

This home was a sanctuary where activists, artists, thinkers, and dreamers gathered strategise, create, and challenge the status quo. It hosted significant discussions and debates, attracting luminaries like Jam Saqi, the resolute trade union leader and general secretary of the Communist Party of Pakistan; Dr. Ang Swee Chai, the renowned orthopaedic surgeon and co-founder of Medical Aid for Palestinians; Meraj Muhammad Khan, a socialist intellectual and founding member of the Pakistan People’s Party; Feica, the sharp-witted cartoonist and human rights activist; Alys Faiz, poet and devoted wife of revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz; and Ahmed Faraz, the iconic romantic poet. United in their quest for a just world, these figures brought unique perspectives to the rich tapestry of thought and action that Aijaz nurtured. Yet, it was Aijaz who anchored these diverse ideas, helping them to take root and flourish with his quiet, guiding influence.

My time in Phyll and Aijaz’s home was transformative. The three floors, filled with books, pamphlets, cassettes, and video recordings, formed a vast library where I was not merely a guest, but a student in the truest sense. Aijaz imparted lessons that transcended traditional mentorship. He taught me how to live fully—how to appreciate the joys of cooking, savour fine wines and spirits, and reconnect with my linguistic heritage through Urdu and my mother tongue, Panjabi/Pothowari. He rekindled my interest in the literary and poetic traditions of the subcontinent, introducing me to the works of Amir Khusrau, Ghalib, Baba Bulleh Shah, Mian Muhammad Baksh, Rabindranath Tagore, Rumi, Allama Iqbal, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Habib Jalib, Fahmida Riaz, and Saadat Hasan Manto. We spent late nights listening to the soul-stirring music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the Sabri Brothers, Abida Parveen, Noor Jehan, Mehdi Hassan, Ghulam Ali, Alam Lohar, and Aziz Mian, with Aijaz translating the profound lyrics, deepening my understanding of the cultural and emotional landscapes they represented.

Learning from Aijaz was a holistic experience, encompassing both the intellectual and the spiritual. Our countless conversations were masterclasses in critical thinking, political theory, and the art of resistance. Yet, it was through observing how he lived—balancing unwavering commitment with deep joy and humanity—that I learned the most. He fiercely believed in hope, even in the most daunting circumstances. I remember many late-night sessions with Aijaz and Ahmed Faraz, who stayed with him during his exile. Aijaz, driven by an unshakeable sense of duty, would encourage Faraz not to let despair overshadow his poetry, always insisting, "Always conclude with hope."

This encapsulates the essence of Aijaz’s philosophy: that even in the darkest times, one must hold onto the light at the end of the tunnel. He taught me that the struggle for justice is not just a fight against oppression but a journey toward a brighter future. In Aijaz, I found not just a mentor, but a guide, a comrade, and a friend who shaped my life in ways I am still discovering. His legacy lives on in every word I write, every act of resistance I take part in, and in the undying hope that fuels my commitment to the cause we both held so dear.

Living under Aijaz’s roof was an education in itself. He was a man of deep conviction who wore his knowledge lightly, teaching by example rather than through pretension. There was no desire to impress—only a humble and profound dedication to living his beliefs. Although he could be less than subtle with those who had exaggerated egos or self-importance, he did not suffer fools gladly, like many of his generation.

Personally, Aijaz's mentorship was both a blessing and a challenge. He often scolded me for not reading enough, playfully taunting me as a "rhetorical sloganizer" on demonstrations. I used to dread his question, "What book are you reading?" On one occasion, I prepared myself with a witty retort: "If books could change the world, then librarians would be the best revolutionaries." His response, however, was classic Aijaz—cutting through my attempt with a sharp wit: "Bari line mari hei" ("That’s a good line"). "Which book did you get that from?"

Aijaz’s dedication to education was not just about accumulating knowledge; it was about empowering those at the margins to think critically about their experiences and to see the world not as it is, but as it could be. He believed that the most radical act was to teach those who had been oppressed to read and write, to help them develop a critical consciousness that could challenge the structures of power that sought to keep them in chains. This was not just a belief; it was a practice that Aijaz lived every day.

In the years that followed, Aijaz continued to be a guiding light in my life. His influence shaped not just my political outlook, but my entire approach to life. He taught me that revolution was not an event, but a process—a continuous struggle that required both critical analysis and unwavering commitment. He rejected orthodoxy, shunning any formula that promised easy answers, and instead called for an ever-evolving analysis, one that responded to the material conditions of the present while drawing lessons from the past.

In a world where the allure of power and recognition often overshadows the quiet, steadfast work of those who labor for justice, Aijaz Kaleem stands as a beacon of selfless dedication to a cause greater than himself. His life was a testament to the belief that true revolution begins not in grand gestures or the pursuit of personal accolades but in the relentless, everyday struggle to uplift the oppressed and challenge the forces of tyranny. Whether braving the harshest elements on Watford Road or standing resolutely against the injustices of racist violence and political repression, Aijaz embodied the spirit of a revolutionary who understood that the fight for dignity and equality is not a sprint, but a lifelong commitment.

Aijaz’s legacy is not written in the annals of history by virtue of high office or public adulation, but in the hearts and minds of those he touched—those who stood alongside him in the trenches of resistance, who learned from his unwavering example that the struggle for a just world is the highest form of human expression. In every leaflet he distributed, in every conversation he had on doorsteps, in every campaign he spearheaded, Aijaz was building not just a movement, but a vision of the world as it could be—a world where dignity is not a privilege but a birthright, and where the oppressed rise not just to survive, but to thrive in their full humanity.

Aijaz Kaleem may not be a name that echoes through the halls of power, but his impact resonates deeply within the communities he served and the broader struggle for justice and equality. He reminds us that the true measure of a revolutionary is not found in titles or accolades, but in the quiet, persistent work of nurturing solidarity, fostering critical consciousness, and challenging the status quo. In this, Aijaz was not just an unsung hero; he was a living embodiment of the revolutionary ideal—a man who understood that the fight for justice is not about personal glory, but about the collective liberation of all people. As we continue to grapple with the forces of oppression and inequality, may we carry forward the lessons of Aijaz’s life, drawing strength from his example to persist, to resist, and to build a world worthy of his unwavering commitment.

As a tribute to Khawaja Ijazullah, Mukhtar Dar presents “Partition of the Heart,” a powerful stage show blending archival footage of Aijaz with live music, evocative soundscapes, multilingual spoken word, dynamic dance, and compelling visual projections. This moving production captures the stories of Partition, offering a timely reflection on the dangers of division and the enduring power of unity.

Partition of the Heart

Wed 30th / Thu 31st Oct

Midlands Arts Centre